|

The State Advisory Council on Indian Education (SACIE) shared its annual report with the State Board of Education earlier this month. The report, which SACIE presents to the Board each year, provides an analysis of American Indian students’ performance regarding end-of-grade (EOG) scores, dropout and graduation rates, and suspension data.

SACIE, established in 1987, analyzes the academic performance of American Indian students in North Carolina’s public schools and provides recommendations to the State Board of Education based on those findings.

Takeaways from the latest report

For the 2022-2023 academic year, 15,865 American Indian/Alaskan Native students were enrolled in North Carolina public schools.

Of this number, 12,538 students were enrolled in one of the 19 school districts that receive funding through the Title VI Indian Education Act of 1972. The data in this report includes all students who self-identified as American Indian/Alaskan Native.

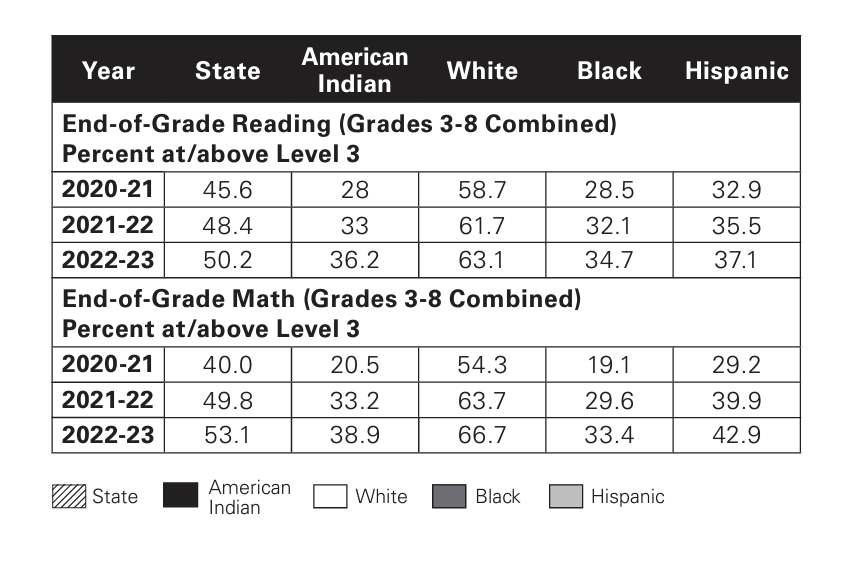

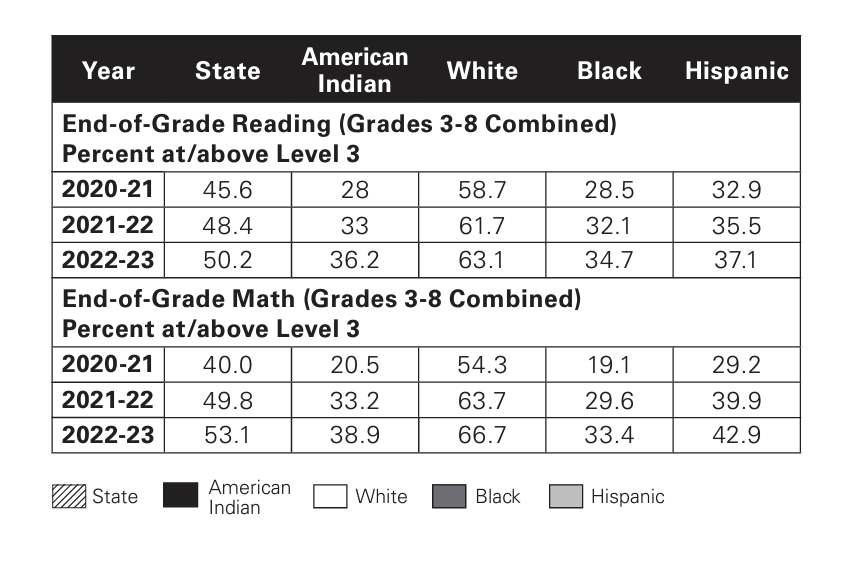

American Indian students showed increased proficiency in reading and math EOG scores, but trail the state average.

The EOG reading data show that American Indian students performed 14 percentage points below the state average. Roughly 36% of American Indian students demonstrated grade-level proficiency in reading, compared to the state average for all students of 50.2%. American Indian students performed 1.5 percentage points above in reading than their Black peers and 0.9 percentage points below their Hispanic peers. American Indian students performed 36.9 percentage points lower than their white peers.

These significant achievement gaps are persistent. Math EOG data show that American Indian students performed 27.8 percentage points lower than their white peers. American Indian proficiency (38.9%) is 14.2 percentage points below the state average.

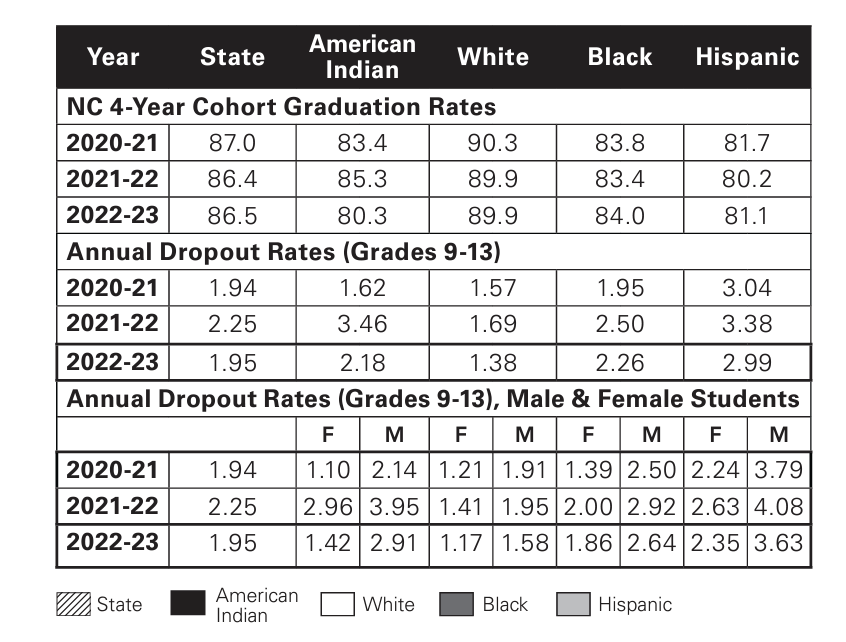

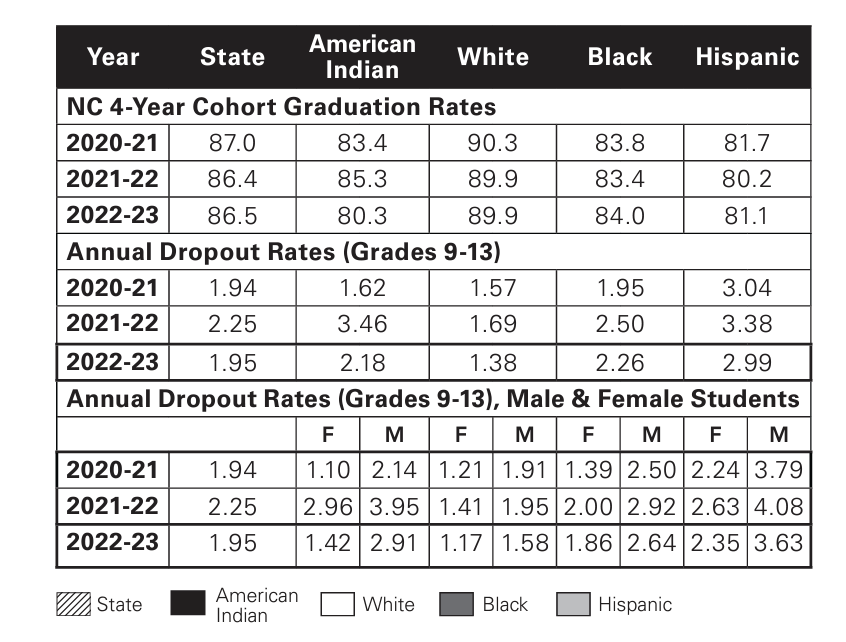

The four-year cohort graduation rate for American Indian students declined by five points from the previous gear, falling from 85.3% to 80.3%. American Indian students trail the state average of 86.5%.

The dropout rate among American Indian students has decreased, but still trails the state average.

SACIE Chair Dr. Tiffany Locklear emphasized that the data in the report show consistent increases in performance, but gaps still persist between American Indian students and their white peers.

“The data starkly highlights the performance gaps between American Indian students and white students,” Locklear said.

The report also highlights end-of-class, Advanced Placement, and SAT/ACT performance data. Check out the full report here.

Locklear commended the progress made, but expressed concern about the remaining gaps that the data reveal.

A look at 2024 recommendations

SACIE provides yearly recommendations to the State Board of Education. This year, the council is once again calling for the N.C. Department of Public Instruction to hire a director of American Indian education services to oversee the Title VI Indian Education programs across the state.

The position was approved last year in the state’s budget, but has yet to be posted or filled. SACIE reiterated its stance that the hiring of a state-level director of American Indian Education should be immediate.

In filling the position, SACIE determined that it would help the Board remain compliant with the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) by ensuring tribal consultation and collaboration with American Indian stakeholders.

The state-level American Indian education director position would help ensure that Title VI American Indian Education programs are maximizing funding and programming, ensure collaboration with NCDPI, and increase engagement between local education agencies and tribes and tribal communities. SACIE prefers that the hiree have demonstrated knowledge of and relationships with North Carolina tribes.

SACIE also recommends that the Board “consult with SACIE and other American Indian leaders to develop shared legislative agendas and funding requests that support legislation and educational policies affecting American Indian students and their achievement in North Carolina’s public schools.” SACIE recommends that the Board seek feedback from SACIE and other members of the American Indian community in the development of state standards and resources, like textbooks and curriculum.

At the conclusion of the SACIE presentation, Superintendent Catherine Truitt spoke up to provide context on the data.

“While we are not closing gaps with our Hispanic, African American, and American Indian students — we are not falling behind,” Truitt said. “And this is unfortunately a pattern that many states are seeing where they are continuing to fall behind during the pandemic and coming out of the pandemic… Everyone in this room (is) committed to ensuring that not only do we continue to see the gains that have been made, but that the gains become such that they are closing gaps.”

Locklear asked the Board to use this data to drive instruction and make the changes necessary for American Indians students and other students of color to succeed.

“It’s a shame, first of all, that I have to continue to push the issue of us making culturally responsive decisions, but it’s still at the forefront of education,” she said. “I just ask that the agency continue to make data informed decisions to close those opportunity gaps for our students because they matter, and again, they’re our legacy.”

SACIE said these recommendations help fulfill the Board’s resolution “to eliminate opportunity gaps by 2025, improve school and district performance by 2025.”

American Indian mascots in public schools

SACIE reiterated its stance on the need for North Carolina public schools to eliminate the use of American Indian mascots, one it has maintained since February 2002, when it passed a resolution calling for the elimination of American Indian mascots and related imagery in North Carolina’s public schools. As of February 2024, 34 schools were found to still have an American Indian-themed logo or mascot.

More about American Indian-themed mascots can be found in Appendices J, K, L, and M of the report.

Credit: Source link